From Silence to Safety – Mapping Incident Reporting in Africa

Strengthening Incident Reporting Systems to Advance Patient Safety in Africa

Background and Overview

Patient safety has long been recognized as one of healthcare’s most urgent global challenges. Landmark studies such as the Institute of Medicine’s ‘To Err is Human’ revealed that tens of thousands of deaths each year in hospitals are caused by preventable medical errors. According to the World Health Organization, one in every 10 patients in high-income countries experiences harm during care, while in low- and middle-income countries, up to four in 100 patients die due to unsafe care, more than half of which is preventable. Medication errors, wrong-site surgeries, retained surgical items, and system failures such as fires or equipment malfunctions continue to claim lives despite decades of protocols and checklists.

Objective 6 of the World Patient Safety Action Plan directly addresses this gap by calling on countries to establish learning and reporting systems and to use data for improvement. However, a 2024 global progress report showed that only 32% of countries had adopted some form of medical incident reporting system. The same report placed Africa’s progress in the “red” (basic) zone, with scores showing how far the region still has to go: 3.3 for incident reporting and learning systems, 3.0 for patient safety information systems, 2.0 for surveillance systems, 1.5 for research programs, and 3.1 for digital technologies, well below the “advanced” threshold of 7. This means most African countries still lack designated people or structures to handle patient safety reporting, with availability below 15% in low- and middle-income settings.

Reporting in many African countries is often voluntary, fragmented, or absent altogether. Many countries still lack national policies or legal frameworks for patient safety incident reporting, while healthcare workers frequently fear blame, punishment, or litigation if they report adverse events. This has contributed to widespread underreporting, making it difficult to identify system failures and prevent recurrence.

However, it is not all doom and gloom.

South Africa has established a national patient safety reporting and learning system, following a 2015 medico-legal summit that highlighted the need to curb rising litigation costs. After a rapid assessment revealed fragmented reporting practices across its nine provinces, South Africa developed its first national guideline for patient safety incident reporting and learning, which came into effect in 2018 alongside a web-based reporting module within its existing Ideal Health Facility Information System. The guideline was revised in 2022 to improve classifications, align with global indicators from the Global Patient Safety Action Plan, and incorporate guidance on just culture to reduce fear of reporting.

Kenya has launched a National Policy on Patient Safety, Health Worker Safety, and Quality of Care (2022), and drafted a Quality of Care Bill that includes provisions on incident reporting. Additionally, Nigeria is building thematic reporting systems within specific domains, even where general medical error reporting remains limited. Ethiopia, on the other hand, has developed incident reporting and management guidelines based on the WHO Minimum Information Model for Patient Safety (MIM PS).

A robust incident reporting system is a foundational requirement for patient safety, and strengthening it requires cultural change, supportive infrastructure, and visible leadership commitment. While Africa has made major strides in expanding access to healthcare, quality and safety have lagged behind. At the end of the day building strong incident reporting systems is a foundational element of transforming healthcare culture.

Challenges to Incident Reporting

Fear of blame and punitive repercussions emerged as one of the strongest barriers to medical error reporting. Staff often stay silent to avoid personal consequences, especially in environments where errors are seen as individual failings rather than system failures. The absence of legal protections and psychological safety means reporting is perceived as risky rather than constructive. This fear-driven culture not only suppresses data but also obstructs opportunities for learning and improvement.

A persistent weakness in many reporting systems is the failure to provide feedback to those who report. When staff report incidents but hear nothing back, they lose motivation to participate. Effective systems must “close the loop” by communicating what actions were taken in response to reports. Sharing learning outcomes not only validates reporters’ efforts but also demonstrates organizational commitment to safety, thereby reinforcing a positive reporting culture.

Building a culture of safety and trust is the first and most critical step. Leadership must explicitly commit to non-punitive responses to error reports. Healthcare workers need assurance that reporting will lead to learning, not punishment. Embedding just culture principles like fairness, transparency, and shared accountability helps shift focus from individual blame to collective learning. Creating psychological safety encourages staff to speak up about near-misses and unsafe conditions before harm occurs.

Alongside cultural change, strengthening infrastructure and systems is just as essential. Countries and facilities need reliable platforms, whether digital or paper-based, to capture incidents, analyze trends, and close feedback loops. Integrating incident reporting data into hospital quality dashboards and national patient safety strategies was highlighted as a way to give visibility and accountability.

Leadership and governance are also non-negotiable elements for sustaining reporting systems. Leaders model transparency when they openly discuss errors and support those involved. Policies must mandate reporting and protect staff who report. Governance bodies should review data, allocate resources, and link reporting outcomes to continuous quality improvement initiatives.

Practical Strategies from Local Frontline Experience

Across Africa, training frontline staff on just culture principles, providing regular feedback, and celebrating learning from incidents have increased reporting rates without fear. Even in resource-limited settings, trust and communication, not expensive technology, are what sustain incident reporting systems over time.

When seeking to change entrenched blame cultures, some staff still fear that incident reports will be used against them during performance reviews or legal proceedings. One of the most viable ways of overcoming this fear is when leadership consistently demonstrates non-punitive responses to error reporting.

An important element of reporting is providing timely feedback to those who report incidents. When staff never hear what happens after they report, trust erodes and reporting declines. Closing the feedback loop by showing how reports led to safety improvements was seen as vital to sustaining engagement.

Finally, improving reporting is not an end goal, but a means to achieving safer care. Incident reports are only useful if they trigger system learning and preventive action. Speakers concluded that strengthening incident reporting systems is a crucial first step toward building safer, more reliable healthcare systems in Africa.

Looking Ahead: Strengthening Incident Reporting In Africa

The future of patient safety in Africa depends on how effectively countries can move from policy to practice in incident reporting. Strong systems are not built overnight, but by consistently fostering cultures of trust, protecting frontline staff, and ensuring that reports lead to visible change. The examples shared in this session, from South Africa’s national reporting platform to Kenya’s policy frameworks and Ethiopia’s structured guidelines, show that progress is possible even in resource-limited settings.

At its core, incident reporting is about valuing transparency, learning, and accountability over silence and fear. Landmark reports like the World Patient Safety Action Plan (2021-2030), and the WHO Patient Safety Fact Sheet underscore that improving safety is not optional but fundamental to quality care. By embedding these principles into everyday practice, African health systems can take a decisive step toward safer, more reliable, and more equitable care.

FOR FURTHER READING

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A new health system for the 21st Century. National Academy Press; 2001.

- World Health Organization, OECD, World Bank. Delivering quality health services: A global imperative for universal health coverage.

- Wilson RM, et al. Patient safety in developing countries: Retrospective estimation of scale and nature of harm to patients in hospital. BMJ 2012; 344: 20.

- Helmreich RL. On error management: lessons from aviation. Br Med J 2000; 320.

- Lachman P, et al. The economics of patient safety. Oxford Professional Practice: Handbook of Patient Safety 2022; 43–54.

- WHO. Minimum information model for incident reporting. WHO Document Production Services.

- Afolalu OO, et al. Medical error reporting among doctors and nurses in a Nigerian hospital: A cross-sectional survey. J Nurs Manag; 29: 1007–1015.

- Mauti G, Githae M. Medical error reporting among physicians and nurses in Uganda. Afr Health Sci 2019; 19: 3107–3117.

- Agegnehu W, et al. Incident reporting behaviors and associated factors among health care professionals working in public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2017. 2019; 8: 182–187.

- Kiguba R, et al. Pharmacovigilance in low- and middle-income countries: A review with particular focus on Africa. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2023; 89: 491–509.

- Ministry of Health Kenya. Saving Mothers’ Lives: Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Death First Report POLICY BRIEF. 2017; 242: 0–3.

- Malande OO, et al. Adverse events following immunization reporting and impact on immunization services in informal settlements in nairobi, kenya. Pan African Medical Journal 2021; 40.

- Peter KS, et al. Common Medical Errors and Error Reporting Systems in Selected Hospitals of Central Uganda. Int J Public Health Res 2015; 3: 292–299.

- Zoghby MG, et al. The reporting of adverse events in Johannesburg Academic Emergency Departments. African Journal of Emergency Medicine 2021; 11: 207–210.

- Department: Health Republic of South Africa. National Guideline for Patient Safety Incident Reporting and Learning in the Health Sector of South Africa. 2022; 1–69.

- Schwappach DL, Boluarte T. The emotional impact of medical error involvement on physicians: a call for leadership and organisational accountability. Swiss Med Wkly 2009; 139: 9–15.

- Nadew SS, et al. Adverse drug reaction reporting practice and associated factors among medical doctors in government hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One 2020; 15: 1–19.

- Yalew ZM, Yitayew YA. Clinical incident reporting behaviors and associated factors among health professionals in Dessie comprehensive specialized hospital, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res 2021; 21: 1–8.

Key Session Highlights

Blame Culture Remains a Barrier

Real-time polling confirmed that fear of punishment is still the biggest obstacle to incident reporting across African health systems.

Leadership is Crucial

South Africa’s journey showed that national reporting systems succeed only with strong leadership commitment and phased, collaborative implementation.

Policy vs. Practice Gap

Countries like Kenya and Ghana have patient safety policies or forms in place, but uptake remains weak without cultural change and enforcement.

Anonymous Reporting Encourages Openness

Kenya’s hospital-level experience with anonymous digital reporting demonstrated that staff are more willing to report when protected from blame.

Fragmentation vs. Unity

Nigeria illustrated the challenge of multiple agencies handling reports; efforts to unify systems are key to reducing duplication and gaps.

From Punishment to Learning

Across all panelists, a shared message emerged: reporting should be a tool for learning, trust, and kindness, not fear or punishment.

quotes from the keynote speakers and panelists

Key Session Takeaways

Incident Reporting Status On The Ground In Africa: Scoping Review

Key Takeaways

1 32% of countries have 60% or more healthcare facilities participating in an incident reporting and learning system

2 Africa’s patient safety incident reporting scores remain in the “basic” red zone (below 4 out of 10).

3 There is an opportunity for improvement across all Objective 6 strategies in African countries.

How African Countries Are Performing When It Comes To Incident Reporting

Key Takeaways

1 Scoping reviews show low medical error reporting across Africa despite awareness of the need to report..

2 Few African countries have a policy direction on patient safety.

3 Electronic health records are still in the early adoption stages in most African countries.

How Kenya Is Trying To Improve On Incident Reporting

Key Takeaways

1 Policy frameworks exist to guide safer care.

2 The gap lies in translating policy into practice.

3 Enablers for implementation need to be identified.

How South Africa Set Up Patient Safety Reporting And Learning Systems

Key Takeaways

2 Getting input from all stakeholders from the start is critical in getting buy-in.

3 WHO support and global workshops enriched South Africa’s process, offering technical guidance and best practices.

Lessons South Africa Learnt From Publishing The National Guidelines For PSI Reporting & Learning

Key Takeaways

1 Leadership commitment is important not only at the national or provincial level, but at all levels within the health facility.

2 Developing a national guideline before developing web- based information systems is critical.

3 Continuous monitoring and feedback to all stakeholders is very important.

How Incident Reporting Is Done In Nigeria

Key Takeaways

1 Multiple channels exist for incident reporting at national and institutional levels.

2 Federal Ministry of Health is the first point of call at national level for hospital-related incidents.

3 Inconsistent reporting practices due to blame culture limit system effectiveness.

How Incident Reporting Is Done In Ghana

Key Takeaways

1 Incident reports are analyzed to train staff and prevent repeat events.

2 Maternal mortality audits within 7 days provide critical lessons..

3 Fear of blame hinders reporting, especially in some districts.

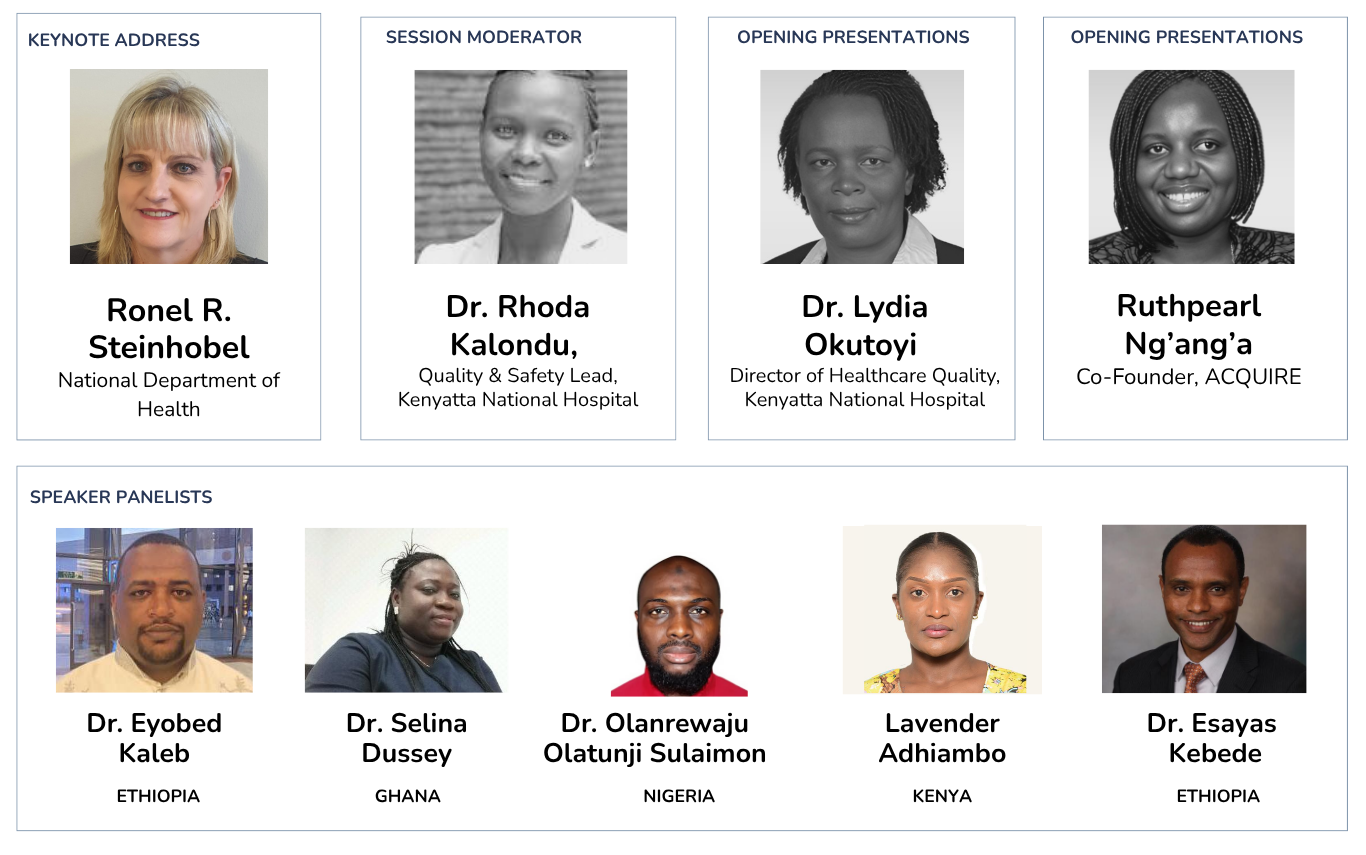

Live Recording, Speakers and Panelists

Strengthening Incident Reporting Systems to Advance Patient Safety in Africa

ACQUIRE’s annual QI Leadership Forum is a continent-wide peer-learning platform on Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Practices in Africa. At ACQUIRE, we believe that improvement is a collective journey.

Join us in working towards more responsive, data-led health systems across Africa.

Email us: [email protected]

Connect with us on our social media platforms: