Strengthening Capacity for Quality: Training Needs Analysis in Quality Improvement.

Background and Overview

Strengthening the capacity of the health workforce is a cornerstone for achieving safer, people-centered healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa. Yet, evidence shows that quality improvement (QI) and patient safety (PS) remain underrepresented in training curricula across pre-service, postgraduate, and in-service levels. World Health Organization highlights that between 10-15% of hospital patients experience harm during care, much of it preventable. These harms often stem less from clinical incompetence and more from systemic weaknesses such as communication breakdowns, teamwork failures, and the absence of structured safety practices. Preparing the workforce to address these challenges requires a deliberate focus on integrating QI and PS into training from the earliest stages of professional education.

Findings from a multi-site Training Needs Assessment (TNA) in Kenya highlight the gaps with stark clarity. The study, conducted across five major institutions including public, private, and faith-based training sites, engaged 476 survey respondents and 34 in-depth interview participants spanning faculty, administrators, frontline workers, and final-year trainees. The results show that while 75% of respondents reported that some aspects of patient safety are mentioned in their courses, less than 50% reported any exposure to quality improvement content. Awareness of institutional safety initiatives is also worryingly low: only 29% of students and frontline staff were aware of patient safety programs in their facilities, and just 20% knew of quality improvement initiatives.

Despite this, there is overwhelming consensus that QI and PS training are essential. Over 96% of respondents agreed these topics should be emphasized in curricula, and 68% recognized personal responsibility in upholding safety and quality. Current training practices show uneven coverage: while 71% reported receiving instruction on adverse events and near misses, only 54% said open disclosure is practiced after adverse events, and fewer than 40% reported that their institutions had systems for anonymous error reporting. Similarly, about 70% indicated they are trained to manage clinical risks, but such training remains fragmented and inconsistently applied.

The study also revealed systemic barriers to integration. Curriculum overload, a lack of qualified faculty, and limited leadership support all constrain the ability to embed QI and PS as core competencies. Only 13% of the studied curriculums offer standalone modules dedicated to these areas, and 20% provide minimal exposure, leaving the majority without structured preparation. Where training exists, it is often theoretical, falling short of equipping students with practical skills. Respondents strongly favored a blended learning approach—combining theory with practice through simulations, team projects, case studies, and mentorship—as well as multidisciplinary teaching and patient-centered learning.

Addressing these gaps is not optional. Embedding QI and PS competencies into health workforce education is critical to building resilient systems that reduce harm, foster accountability, and empower providers to co-produce safer care with patients and communities. Leadership buy-in, faculty capacity building, and curriculum reform are central to moving from fragmented exposure to structured, sustained integration of QI and PS across all levels of training.

Key Themes

Leadership plays a decisive role in creating the conditions for quality improvement and patient safety to take root. When leaders are not empowered with the right knowledge and mindset, frontline training efforts often fail to translate into action. Effective leadership requires not only being informed about initiatives; but it also demands mentorship, coaching, and the ability to create enabling environments where healthcare workers can apply what they learn. Without leadership buy-in, efforts risk remaining fragmented and unsustainable.

Readiness assessments are essential before rolling out training. Too often, programs are introduced without examining the organizational environment, team preparedness, or alignment with existing systems. By analyzing job descriptions and mapping responsibilities, readiness assessments reveal whether staff at different levels (nurses, managers, or administrators) are positioned to apply quality improvement principles in their daily work. However, the widespread use of generic job descriptions undermines this process, as roles often do not match actual tasks on the ground. In such cases, readiness assessments must also include role clarification, ensuring that training is contextualized and aligned with real functions.

By systematically assessing readiness, institutions can ensure that quality and safety training is introduced in contexts where it can be embedded, sustained, and tied into broader strategies.

The availability of basic resources remains a persistent barrier. Facilities struggling with essentials such as handwashing supplies or food for patients cannot reasonably be expected to advance quality improvement goals without creative problem-solving. Institutions must encourage leaders to think beyond resource constraints, mobilizing local partnerships and internal assets to meet foundational needs. Without these basics, even well-designed training programs risk collapsing under the weight of everyday challenges.

A strong foundation of knowledgeable healthcare workers is also critical. Staff must be competent not only clinically but also in the principles and tools of quality improvement. While many workers gain exposure to QI concepts, coaching and mentorship are required to help them apply these principles in practice. Without such support, knowledge remains theoretical, and the opportunity for meaningful change is lost.

Gaps in data management continue to undermine progress. While outcomes are often measured, process-level data—the information that shows whether changes are working—is less consistently collected. Even where data is gathered, interpretation remains weak, with teams celebrating single data points rather than analyzing trends. Closing this gap requires practical training in data collection, analysis, and interpretation, ensuring teams can use evidence to guide improvement.

Another gap lies in documentation. Despite widespread activity, few healthcare workers write stories, abstracts, or reports about their quality improvement efforts. As a result, valuable lessons remain siloed, and opportunities for cross-learning are lost. Encouraging documentation and dissemination not only supports learning but also builds institutional memory and strengthens the visibility of successful initiatives.

Curriculum gaps are a recurring theme. While quality improvement and patient safety appear in many training programs, they are scattered across various modules and rarely presented as stand-alone units. This fragmented approach dilutes the emphasis on QI and PS, leaving students unclear about their importance. Institutions need to integrate these topics more coherently, with clear modules, structured content, and consistent assessment.

A tendency to stop at quality assurance rather than pursuing quality improvement also hinders progress. Many institutions have protocols and documentation processes in place, but these are aimed at maintaining current standards rather than continuously seeking better outcomes. A shift in mindset is needed; from compliance and assurance to ongoing improvement and innovation.

Clinical placements expose another gap, as students often encounter environments that do not reflect the theory they have been taught. Inconsistent practices, lack of structured incident reporting systems, and limited involvement of students in safety processes weaken the learning experience. Aligning clinical sites with the standards emphasized in training is vital to ensure that students see consistency between theory and practice.

A lack of systems thinking continues to limit progress. Too often, errors are attributed to individuals rather than seen as the result of systemic weaknesses. This narrow view prevents institutions from addressing root causes and building safer systems. Embedding systems thinking in both training and practice encourages a shift from blame to solutions, fostering a culture where patient safety and quality improvement can thrive.

Post-Panel Discussion

The importance of extending the focus of patient safety beyond healthcare institutions to the community level was emphasized. Population health approaches that begin in schools and community settings can empower citizens with the knowledge and confidence to demand safe care. When communities understand what quality and safety entail, they hold providers accountable, influence health-seeking behaviors, and act as first responders in emergencies. This demand-side pressure complements institutional efforts and ensures that safety is reinforced from both directions; inside facilities and within the community.

Another key issue raised is the role of supervisors in sustaining improvements. Training frontline workers without the engagement of their supervisors weakens impact, as oversight and support are often absent. Addressing this requires innovative approaches to supervisor engagement, such as modular or bite-sized sessions, integration of quality metrics into supervisory roles, and, critically, the allocation of protected time for QI activities. Without explicit commitments in institutional terms of reference, frontline staff are often denied the time needed to implement what they learn.

The discussions also highlighted the role of regulatory bodies as a missing link. While training institutions prepare students, regulatory councils rarely embed patient safety and quality as core competencies for licensing or relicensing. Integrating QI and patient safety into competency frameworks and linking them to continuing professional development points would create stronger incentives for healthcare workers and institutions to prioritize these areas. Without regulatory alignment, the pipeline from training to practice remains fragmented, and improvements risk being lost after graduation.

Sustainability emerged as another central concern. Participants cautioned against training programs that focus only on knowledge transfer without assessing whether systems exist to support implementation. Readiness assessments, role clarity, and organizational buy-in are critical before training begins. Effective follow-up mechanisms such as communities of practice and periodic mentorship provide continuity, enabling facilities to monitor progress and address gaps over time. These mechanisms ensure that training does not end in the classroom but translates into tangible improvements in patient safety and quality across healthcare systems.

Building a Workforce for Safer Care

Strengthening capacity for quality improvement and patient safety is a practical necessity for building health systems that are safer, more trusted, and more resilient. Training needs analyses highlight where progress has been made, but also where critical gaps persist: fragmented curricula, limited faculty expertise, inadequate supervisory engagement, and weak regulatory alignment. Addressing these challenges requires leadership buy-in, readiness assessments, and systems that support learning beyond the classroom. More importantly, institutions of clinical practice need to be ready to integrate healthcare workers who have been trained on quality improvement practices to help turn theory into practice.

By embedding QI and patient safety into pre-service education, in-service training, and regulatory frameworks, institutions can move from scattered initiatives to sustainable practice. Communities, supervisors, and regulators must all be part of this effort, ensuring that safety is reinforced from the classroom to the clinic, and from the facility to the community. The path forward is clear: equip every healthcare worker not only with clinical skills, but also with the tools to continuously improve, reflect, and co-produce safer care for all.

Key Session Highlights

Readiness Determines Success

Introducing QI training without assessing organizational readiness risks failure. Role clarity, job descriptions, and alignment with existing systems are vital for embedding new practices.

Resource Gaps Undermine Training

When facilities lack basics like clean water or patient food, quality improvement initiatives struggle. Creative problem-solving and partnerships are required to address these foundational needs.

Weak Data Use Slows Progress

Process-level data is often neglected, and teams may celebrate single data points instead of analyzing trends. Training in data collection, analysis, and interpretation is essential for informed improvement.

Documentation Builds Collective Learning

Encouraging reporting and dissemination strengthens institutional memory and spreads good practices.

Curriculum Gaps Persist

QI and patient safety are often scattered across training programs rather than offered as structured modules. This fragmented approach dilutes their importance and weakens student preparedness.

Theory-Practice Disconnect in Clinical Sites

Aligning training curricula with real-world clinical environments ensures that safety and QI principles are reinforced.

quotes from the keynote speakers and panelists

Key Session Takeaways

Next Steps After Quality Assurance Training In College

Key Takeaways

1 Quality assurance focuses on maintaining standards; quality improvement aims for ongoing enhancement.

2 Continuous improvement should replace “checklist” compliance in healthcare education.

3 Embedding QI concepts in training prepares future professionals for system-level thinking.

Importance Of The Environment And Involving Leadership When Offering QI and Patient Safety Training

Key Takeaways

2 Leadership engagement is critical as they enable frontline staff to act.

3 Training should be embedded within organizational strategy, not treated as an isolated event.

Key Drivers In Championing QI For Healthcare Workers

Key Takeaways

2 Reliable data systems are essential to track progress and guide decision-making.

3 Healthcare workers need both QI knowledge and strong clinical skills to drive change.

Current Curriculum Status From A TNA Done For QI and Patient Safety In Kenya

Key Takeaways

2 Embedding patient safety and quality into curricula is essential for shaping competent health professionals.

3 Structured learning ensures consistency and sustainability in quality care education.

Existing Gaps In Quality Improvement In Healthcare

Key Takeaways

2 Teams must learn to interpret data trends over time, not rely on single data points.

3 Writing and documenting QI experiences strengthens learning and knowledge sharing.

How To Identify The Kind Of Support To Give In The Application of QI and Patient Safety

Key Takeaways

2 Role clarity helps align QI goals with daily responsibilities across all staff levels.

3 Generic job descriptions can hinder effective QI implementation and accountability.

How Learning Institutions Can Better Train Students On QI and Patient Safety

Key Takeaways

2 Leveraging online learning platforms can overcome time constraints and expand access to QI resources.

3 Practical exposure through small-scale QI projects helps students apply theory to real-world scenarios.

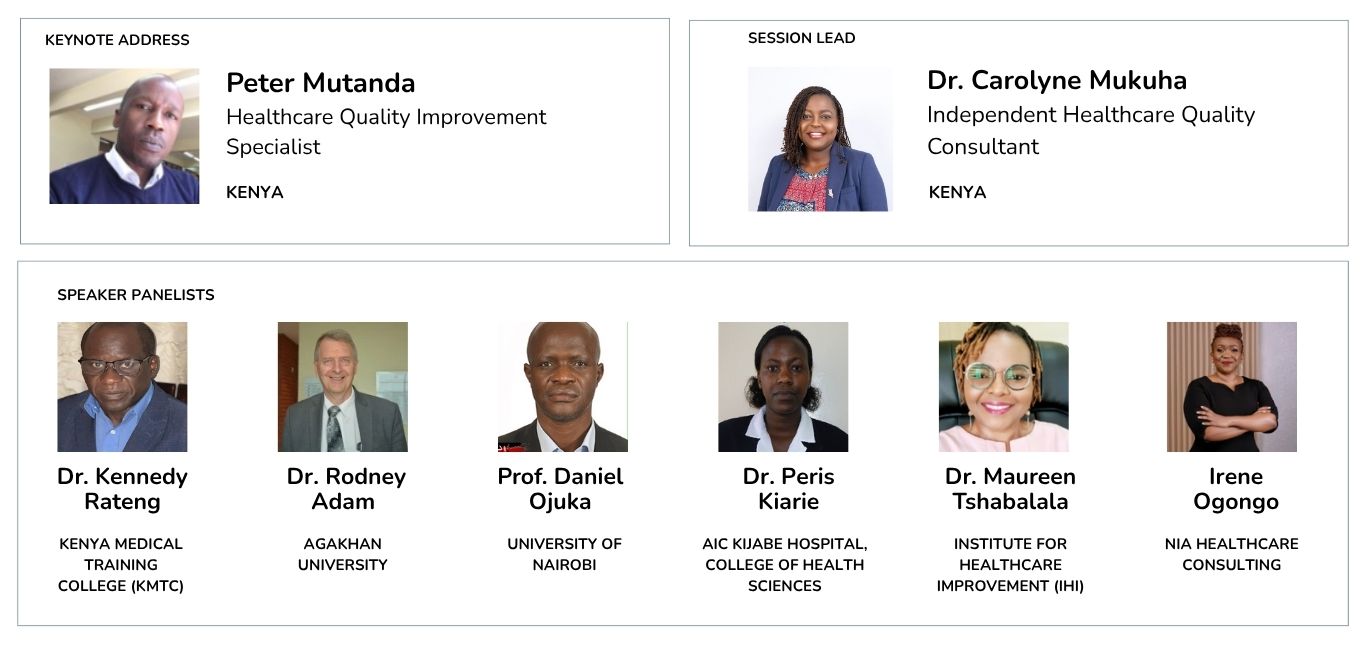

Live Recording, Speakers and Panelists

Strengthening Capacity for Quality: Training Needs Analysis in Quality Improvement.

We invite you to share your experiences, insights, or reflections on training gaps, capacity building, and how we can better prepare healthcare workers to lead change. Your contributions can shape the future of health workforce training and strengthen systems across Africa and beyond.

Join us in working towards more responsive, data-led health systems across Africa.

Email us: [email protected]

Connect with us on our social media platforms: